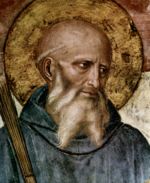

There was a man of saintly life;

blessed Benedict was his name,

and he was blessed also with God’s grace.

(St. Gregory the Great: The Life of St. Benedict)

Unlike other

monastic figures of the 5th century, St. Benedict is not mentioned by any of his contemporaries. For our knowledge of him we are entirely dependent upon a single source, the

“Dialogues” of Pope Gregory the Great, a work in four books written in 593-594, whose second book is entirely devoted to Benedict.

Before giving a few details about the Saint’s life, the fact should be stressed that Gregory’s writing is not what today we could classify as a ‘historical’ or ‘biographical’ work. Instead his Life of St. Benedict strives to bring out Benedict’s gift of prophecy and his power of working miracles because these particular gifts are the characteristics of the men of God as depicted in the Bible. In other words, facts and chronology in the life of St. Benedict are not the primary matter of interest for St. Gregory, his chief preoccupation being to use -as it were- St. Benedict to teach the readers the stages through which a man advances toward God.

So the stories in the life of St. Benedict have a symbolic intent, for example, they show that fruitfulness comes from what at first sight seems sterile; life comes forth from death, a man who concentrates upon his own sanctification becomes an instrument of God for the good of mankind, etc.

And since the miracles performed by St. Benedict were the outflowing of his prayer, one cannot undervalue the place of prayer in his life. Indeed, prayer was a central feature in his life, and he expected it to be the central feature in the live of his monks as well. In this regard the Rule states that ‘nothing should be accounted of more importance than the work of God’, that is, the common prayer of the community.

This being said, the following is a brief presentation of the most salient facts in the Saint’s life.

Benedict was born in 480 in the mountain-region of Norcia, northeast of Rome. He was sent to Rome for school and there he experienced the religious conversion that led him to ‘leave’ the world in order to re-enter it as a new man. He is depicted at first living with what seems to have been a group of ascetics at Enfide (now Affile), east of Rome, then in utter solitude for three years at Subiaco.

The Monastery of Subiaco, built in the same wall of rock as Benedict’s cave

After a bitter experience as head of a group of monks who had requested him to be their leader but then showed themselves unwilling to live a sound Christian life, he returned to Subiaco, where he was joined by numerous disciples for whom he established twelve monasteries of twelve monks each.

After these monasteries had been firmly established, Benedict left this region with a few disciples and founded a monastery on top of the mountain rising above Cassino, some 120 kilometers south of Rome on the way to Naples.

The Abbey of Monte Cassino

In Monte Cassino he acquired a widespread reputation as a holy man invested with divine gifts, and died -or to use the symbolic language of St. Gregory- he moved from earth to heaven around the middle of the sixth century.

Surrounded by his disciples, Benedict while praying breathed his last

(Miniature at Monte Cassino, dating from the eleventh century)

St. Benedict wrote a Rule for monks (which came down to us under various names such as, Regula monasteriorum, Regula monachorum, Regula Sancti Benedicti, etc.), which, in the words of his biographer St. Gregory, is ‘notable for its discernment’. Actually it is in the reading of the Rule that one comes to grasp the real mind of Benedict, who certainly appears to have been an uncommon organizer but, even more than that, in the Rule’s attention and respect for the individual, Benedict shows himself to be a considerate father to his monks.

As it is widely recognized, it was through monks that christianization of Europe was carried on during the Middle Ages; a process that infused into the new emerging culture not a few of the ‘Benedictine’ values contained in the Rule, such as manual work viewed no more as something to be left for uncultured slaves but as a humanly enriching, indeed as a sanctifying occupation; a refreshing concept of the relation between sacred and profane that at that time were considered as two opposing principles; etc. Indeed, the famous Lutheran historian Goltzen, enumerating the pillars on which the whole of western Christianity’s scaffolding leans, straight after the Bible puts the Rule of St. Benedict. It is doubtless for such an in-depth contribution in the moulding of Europe’s civilization that St. Benedict was proclaimed Patron Saint of Europe.

The Rule of St. Benedict and his Life (both in Bangla) are downloadable from this site at Scriptorium - Patristic.